Lucky scientific discoveries

Recently I had been searching the internet for laboratory accidents. I soon realised that most websites were not talking about funny little incidents. The reality of lab accidents is actually quite horrific and a good reminder for health and work safety protocols.

This also reminded me of my lab work during my Bachelor’s Thesis. I was using methanol and carried it from one building to another. The building I was working in had five laminar flows, but no flow hood. Also, I did not receive any inductions or safety protocols and was completely unaware why methanol should always be stored in a flow hood. In my naivety, I assumed it is because of the smell. The two lab technicians, both in their 40s or 50s, must have thought similarly. Because soon after the smell spread throughout the room, they told me to put the bottle of methanol inside the fridge. From memory, I had used the bottle again the next day, put it back into the fridge and then returned it on the second day to its previous location under a flow hood. Phew…. I heard about the dangers of methanol and its storage conditions sometime later on. I still get shiver just thinking about this entire event.

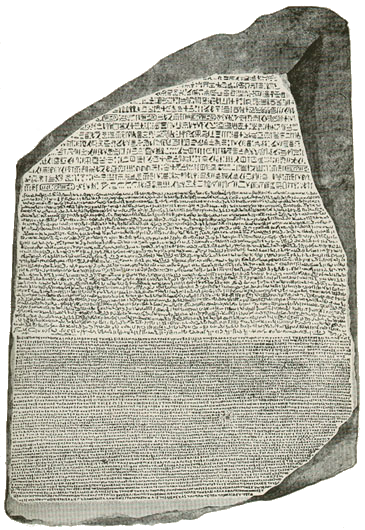

I realised that most “famous” lab accidents are not funny and that I had been very lucky myself. So, I did the only reasonable thing and distracted myself by turning my search approach towards lucky scientific discoveries. Low and behold, there is a whole Wikipedia article dedicated to this topic. This is not just a listing of coincidental discoveries, but actually brings forward theories which estimate that 30 to 50 % of all scientific discoveries are accidental (REF ). And there is another Wikipedia article that actually lists many examples: Newton’s discovery of the gravity, Nobel’s blasting gelatine and even archaeological discoveries like the Rosetta Stone or Pompeii.

Rosetta stone, discovered in 1799 by French soldiers while building a fort in Egypt.

Now I wonder about a lot of different things. If up to 50 % of scientific discoveries stem out of lucky events, should we only focus on valid experimental hypotheses? Or should we rather keep an open mindset to “glitches” in the methodology. We should always keep in mind that lucky discoveries do not sound like luck after all, but more like hard work and dedication. They are merely the result of a mindset that is tuned into receiving events, rather than hoping for outcomes. All this is easier said than done, and perhaps the scientific mind is unconsciously affected by previously written research proposals and their goals and objectives. Even more so, it is affected by the overwhelming pressure to submit scientific publication as soon as possible. And after all, scientists are also human beings that carry their personal and social life into the lab, distracting oneself from the actual work.

I enjoy solving problems, and in this case, I wanted to discover ways to enhance the mind’s ability to realise any serendipitous events that could lead to lucky discoveries. Not too long after, I remembered parts of a talk by Alan Watts which resonated with me a lot:

Trust the Universe

“You do not know where your decisions come from. They pop up like hiccups. [...] So when we decide, we are always wondering: Did I think this over long enough? Did I take enough data into consideration? And if you think it through you find, you never could take enough data into consideration. The data for a decision in any given situation is indefinite. So, what you do, you go through emotions. Or thinking out what you will do about this. […] But we fortunately forget the variables that would have interfered with this coming out right. It is amazing how often this works. But worriers are people who think of all variables beyond their control and what might happen. So, when you make the decision and it works out all right, then I think very little of it has much to do with your conscious intent and control.” (Alan Watts)

Unarguably, most scientific experiments have been planned and designed with the highest amount of conscious intent and control. But no matter how much, we never have full control over an experiment. This is true for lab experiments as much as for greenhouse or field experiments. And if scientists want to worry about an experiment, they will always find reasons to do so. This, however, would affect anyone’s ability to perceive these important “lucky” events. Worrying can be described as one way to maintain the belief of a negative future outcome. And worrying does not prevail as an effective preparation for these future events.

Alan Watts also offers a solution to this inherent problem of decision making. In my opinion, of most relevance is his explanation about the daoistic concept of Wu-wei. Wu-wei, according to Alan Watts, can be best (and shortest) described as “not to force anything”. In the Dao De Jing, one of the central texts of Daoism, it is described as “The way never acts yet nothing is left undone”. This force-vacuum does not deplete actions but leads to effortless actions, or actionless actions. A more modern approximation of this concept is described as “being in the zone”. This refers to the state where no distracting thoughts are interfering with the focused attention to actions.

Imagining myself in a work environment, this state would be highly sought-after. Finishing one task after another without disturbing thought patterns would increase productivity immensely. Obviously, productivity and efficiency is what everything is about, right? But wait a moment, can we reach Wu-wei when we treat it is as another method to increase every day’s productivity? After all, we would force our mindset towards reaching the flow-state, which means putting efforts into our actions. It is as paradoxical as the Buddhistic desire to reach desirelessness. This makes sense if we come back to the beginning thoughts of this exception of Wu-wei: Tuning our mind into the receiving-state of serendipitous lucky events. If we were to put our mental preparations into the Material and Methods of our manuscript, like we include the experimental design or statistical analysis, we would have achieved nothing. It would just be another effort to control all the indefinite variables that go into conducting an experiment.

What would be a solution? According to our good friend Alan Watts, it would be to let go and trust the universe: “To have faith is to trust yourself to the water. When you swim you don’t grab hold of the water, because if you do you will sink and drown. Instead, you relax, and float.” Similarly, scientists should trust in their knowledge and their colleague’s expertise. Experiments are set-up according to the best of knowledge and conducted accordingly. The results are interpreted objectively and without desired outcomes. This approach could clear the vision towards any unexpected outcomes, which could then be more important than the actual experiment.

Alan Watts also says: “A scholar tries to learn something every day; a student of Buddhism tries to unlearn something daily.” Maybe we should do both. Maybe scientists should learn something new every day, but also unlearn a disadvantageous pattern every day. Judging from my academic and personal lifestyle, there are plenty of patterns worthwhile being unlearned.

What about unlucky scientists?

Thomas Midgley (1889 to 1944) is commonly considered as the unluckiest scientists. After all, he invented the use of lead in gasoline as an antiknock agent (tetraethyllead). Later on, he invented chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) as refrigerant in domestic fridges and ACs. To promote both of his products, he inhaled large amounts of lead gas and CFC to show their safety. So exactly how unlucky was he? It is said that while recovering from lead poisoning after his safety demonstration, he said on a phone call to Charles Kettering in 1923: “Can you imagine how much money we're going to make with this? We're going to make 200 million dollars, maybe even more”. Pretty far away from the principles of Wu-wei, if you ask me. Maybe we can use Thomas Midgley as a good case example. I know that causality is not correlation, but for the sake of keeping this blog article short, it serves as a good example of how greed and forced actions result in unlucky discoveries.

Antiknock agent tetraethyllead. Picture provided by user Plazak via Wikimedia.